#colin pantall

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Left, screen captures from Muscle, directed by Hisayasu Satô, 1989. Via. Right, photograph by Herbert List, Hands, violin, and bow of the king of waltz, Johann Strauss. From the series Panoptikum, Vienna, 1944.

While Signal, the dominant propaganda magazine of the Third Reich, focussed on delivering the Nazi ideological message, Tele turned to the cultural life of Europe. It was a magazine that would “employ softer tones… to promote sympathy for Germany,” that would show a selective appreciation of history, culture, and art.

It was a magazine that showed Germans in a flattering light, as people who appreciated music, art, and the finer things in life, people who, before the war, you might have sat next to during an orchestral performance, people whose not-so-hidden message was, ‘Perhaps we will one day do the same once all this nonsense is finished.’ The editorial policy of the magazine can be summed up as, ‘Let’s not talk about the war.’ Indeed, a picture from the magazine’s penultimate issue was captioned, ‘Let’s just not talk politics.’

That was how, early in 1944, List came to travel to Vienna to meet up with the editors of Tele (who had moved from Berlin due to ongoing air raids), says Richter. “There, he fell in love with the Panoptikum, and suggested that he wanted to do a photo essay on it.”

A waxworks museum in Vienna’s Prater Amusement Park, the Panoptikum was founded by Hermann Präuscher in the 19th century, and showed a variety of waxworks in a lurid mix of fame, horror, sex, murder and anatomical detail in equal measure.

List had photographed waxworks and catacombs earlier in his career. He had a surrealist fascination for the way the dead eyes and glossy skin of the waxworks were offset by their expressive faces and lifelike poses. Like photography itself, these figures had a surface you couldn’t quite get to grips with, and hidden depths which aroused a sense of unease and the uncanny in the viewer. They existed in a half-world between life and artifice, between fantasy and reality.

Colin Pantall, from Herbert List’s Panoptikum - Colin Pantall speaks to Peer-Olaf Richter, Director of the Herbert List Estate, about the strange and surreal "Panoptikum," a photobook that was first conceived in Vienna in 1944, and published 79 years later, in Magnum, September 29, 2023.

--

(...) the dream experience cannot be isolated from its content. Not because it may uncover secret inclinations, inadmissible desires, nor because it may release the whole flock of instincts, nor because it might, like Kant’s God, 'sound our hearts'; but because it restores the movement of freedom in its authentic meaning, showing how it establishes itself or alienates itself, how it constitutes itself as radical responsibility in the world, or how it forgets and abandons itself to its plunge into causality. The dream is that absolute exposure of the ethical content, the heart shown naked.

Michel Foucault, from Dream, Imagination, and Existence, 1954. In his first published text, Foucault discusses the subject matter of Traum und Existenz (Dream and Existence) by Ludwig Binswanger, 1930. Via.

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Colin Pantall

38 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Colin Pantall

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Colin Pantall

1 note

·

View note

Text

'all quiet on the home front' - Colin Pantall.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

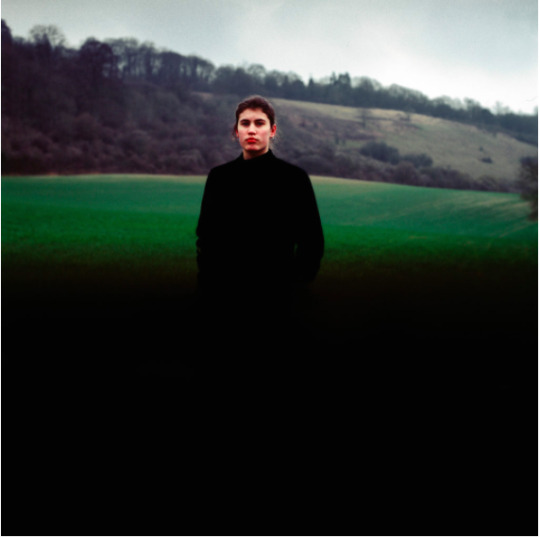

Colin Pantall

From the series All Quiet On The Home Front

Courtesy of the artist

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

From the book All Quiet on the Home Front

© Colin Pantall

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

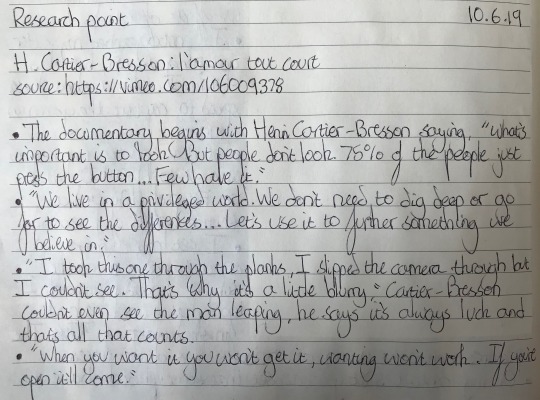

Research point

H. Cartier-Bresson: l’amour tout court

Source: https://vimeo.com/106009378 (1)

The documentary begins with Henri Cartier-Bresson saying, “what’s important is to look. But people don’t look. 75% of the people just press the button... Few have it.”

“We live in a privileged world. We don’t need to dig deep or go far to see the differences... Let’s use it to further something we believe in.”

Behind the Gare Saint-Lazare by Henri Cartier-Bresson, 1932 (2)

“I took this one through the planks, I slipped the camera through but I couldn’t see. That’s why it’s a little blurry,” Cartier-bresson couldn’t even see the man leaping, he says it’s always luck and that’s all that counts.

“When you want it you won’t get it, wanting won’t work. If you’re open it’ll come.”

“One shouldn’t think about it but the basis is geometry... We know where the golden section falls... it’s in the eye. I go for form more than light, form comes first.”

The writer Yves Bonnefoy comments on Cartier-Bresson’s ability, “when others are distracted and unobservant, Henri is on the lookout, ready to react, not even needing to stop in order to help the geometry - as he calls it - play its obvious decisive role in framing the scene.”

Cartier-Bresson describes photography as, “sensitivity, intuition, a sense of geometry; that’s all there is to it.”

Painter Avigdor Arikha says, “the problem is that our gaze is always conditioned by recognition. In other words, we only see what we can recognize... In a portrait what interests or obsesses me is to capture the person, more than just resembling the person it has to be the person I take and put on the canvas.”

Henri Cartier-Bresson never wanted the people he photographed to realize what he was doing. When the models know that someone is observing them, they pose, they put on masks, they lose their spontaneity.

Cartier-Bresson finishes off the documentary by saying, “what’s important is what comes next, erase the past... Put yourself into question. It’s essential.”

Photography: A Critical Introduction by Liz Wells

(pgs. 91-92, 343-344)

Source: https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ucreative-ebooks/reader.action?docID=1968918# (3)

Liz Wells Writes:

Documentary photographers took considerable pains to control the nature of a scene without making any obvious change to it.

Therefore, Henri Cartier-Bresson lay in wait for all the messy contingency of the world to compose itself into an image that he judged to be both productive of visual information and aesthetically pleasing.

This is called ‘the decisive moment’, a formal flash of time when all the right elements were in place before the scene fell back into its quotidion disorder.

Increasingly, documentary turned away from attempting to record what would formerly have been seen as its major subjects. Instead it began to concentrate on exploring curtural life and popular experience, and this often led to representations that celebrated the transitory or the fragmentary.

Cartier-Bresson believed ‘the endeavour to make great statements gave way to the recording of little, dislocated moments which merely insinuated that some greater meaning might be at stake.’

Cartier-Bresson’s humanist work is often regarded as documentary or photojournalism but he is also seen as working outside the constraints of lables of this kind.

Photographer and theorist Allan Sekula believes, “documentary is thought to be art when it transcends its reference to the world, when the work can be regarded, first and foremost as an act of self-expression on the part of the artist.”

To have to engage with particular conventions, technical processes and rhetorical forms in order to authenicate documentary undermines the notion of the objective camera and with it, one might imagine, any claim of documentary to be any more truthful to appearances than other forms of representation.

The decisive moment is most often used in portraiture and documentary. Landscapes are generally not staged, and unlike photojournalism, there is rarely a sense of ‘decisive moment’ when contents and aesthetics come together to create a telling image.

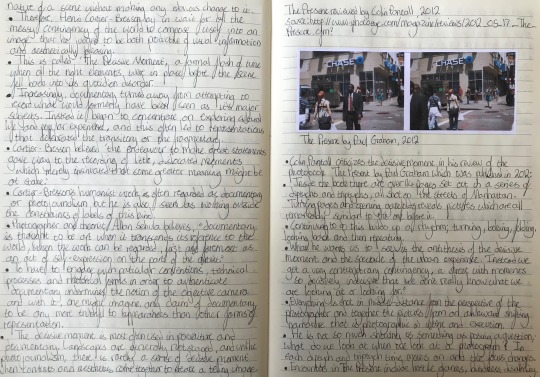

The Present reviewed by Colin Pantall, 2012

Source: https://www.photoeye.com/magazine/reviews/2012/05_17_The_Present.cfm? (4)

Colin Pantall criticizes the decisive moment in his review of the photobook The Present by Paul Graham which was published in 2012:

Inside the book there are over 114 pages set out in a series of diptychs and triptychs, all shot on the streets of Manhattan. Turning pages and opening gatefolds reveals pictures which are all remarkably similar to the one before it.

Continuing to do this builds up a rhythm; turning, looking, folding, looking back and then repeating.

“What he wants us to see is the antithesis of the decisive moment and the spectacle of the urban experience. Instead we get a very contemporary contingency, a street with moments so decisively indecisive that we don’t really know what we are looking at or looking for.”

Everything is shot in middle-distance from the perspective of the photographer and together the pictures form an awkward shifting narrative that is photographic in intent and execution.

He is not so much showing us something as posing a question; what do we look at when we look at a photograph? In each diptych and triptych time moves on and the focus changes.

Encounters in The Present include hostile glances, blindness, disability, poverty and wealth. Graham doesn’t isolate and iconicize his subjects, instead he remakes them in his own image and that is what makes the book intersting; the fact that the pictures don’t look like anyone else’s.

“There is a poverty of experience and environment here, an existence that appears deprived environmentally, emotionally and culturally. That’s the narrative; it’s a miserable life. Welcome to the Present.”

The Present by Paul Graham, 2012

Zouhair Ghazzal’s take on the decisive moment, 2004

Source: http://zouhairghazzal.com/photos/aleppo/cartier-bresson.htm (5)

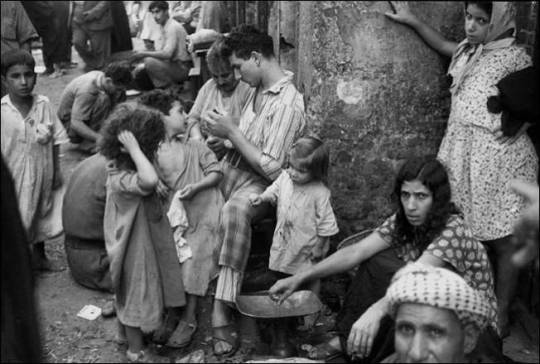

Jewish neighborhood of Baghdad by Henri Cartier-Bresson, 1950

The words of Zouhair Ghazzal:

“The decisive moment is more of a cliché than a reality, even for its own creator, it still has the status of a myth with too much of an unconscious impact on photojournalism to be dismissed too easily.”

Practically every serious photographer in the last couple of decades has had to forego the decisive moment to be able to create and produce in territories where there are less and less decisive moments, and more repetitive urban landscape.

At its core, the notion of decisive moment does not seem pretentious at all, the decisive moment is that infinitely small and unique moment in time which cannot be repeated, and that only the photographic lens can capture.

Even though it is possible for landscapes and buildings to be captured at their most decisive moments, Cartier-Bresson’s photography is at its best with bodies and their gestures, there’s something anecdotic in them.

“The decisive moment works best when the sudden cut in time and space that the photograph operates through the release of the shutter is meaningful, as it narrates to us in a single frame the before and after; while other photographs of the decisive type remain anecdotal, with no precise meaning, or with no meaning at all, relying instead on the juxtaposition of bodily gestures with symmetries created by light and space.”

Some of the top photographers of the last few decades, which willy-nilly did not base their photography on the decisive moment, would argue that the latter’s major weakness was precisely its sole reliance on gestures.

Modernity came all too abruptly to cities such as Baghdad, expanding them indefinitely, and creating for the most part urban landscapes that are so monotonous and dull, that no decisive moment would be able to capture.

Independant research

Sources: The Photo Book, published by Phaidon Press, pgs.10, 97, 225, 242, 262, 329 (6)

http://100photos.time.com/photos/eddie-adams-saigon-execution (7)

https://www.mindenpictures.com/search/preview/blue-wildebeest-connochaetes-taurinus-herd-descending-cliff-during/0_00114286.html (8)

http://www.cape.ag/?p=1252 (9)

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/may/27/snap-judgment-how-photographer-jacques-henri-lartigue-captured-the-moment (10)

https://www.icp.org/browse/archive/constituents/barbara-morgan?all/all/all/all/0 (11)

Saigon Execution by Eddie Adams, 1968

This photograph shows Colonel Loan of the South Vietnamese police shooting dead the Vietcong suspect in the checkered shirt. It captures the exact moment that the bullet enters the man’s head and was taken during a minor skirmish in the Chinese section of Saigon.

After shooting the suspect, the general justified the suddenness of his actions by saying, “If you hesitate, if you didn’t do your duty, the men won’t follow you.”

The freezing of the moment of Lem’s death symbolized for many the brutality over there, and the picture’s widespread publication helped galvanize growing sentiment in America about the futility of the fight.

Addam’s photo started off a more personal and intimate level of photojournalism in war zones. Three decades later he commented, “Still photographs are the most powerful weapon in the world.”

Petroglyph and Star Trails, Sonora, Mexico by Linda Connor, 1991

In this photo the earth is represented by the foliage in the foreground and the outcrop of rock jutting from the corner. It looks as though it is turning beneath the sky at night.

There are star trails in this photo which indicates it was taken over a very long exposure, probably for several hours or as long as it took to capture the movement of the stars.

Different intensities of light emerge and the purpose of this was to show how different surfaces and textures are illuminated by starlight. The rock itself is highlighted.

In the introduction to her book, Solos, published in 1979 she says, ‘creative energy is an elusive force which is my privilege to serve and transform.’

I believe that despite the long exposure used in this photograph, it can still count as a decisive moment because it has captured a specific moment in time, mapped by the stars, that cannot be replicated by the human eye alone.

Horned Avalanche by Mitsuaki Iwago, 1986

This photo was shot in the Serengeti National Park in Tanzania and features a herd of wilderbeest who are migrating across a river. At the time this photo was taken, there were over a million and a half of these animals in the National Park. Hundreds drowned in these events.

Iwago studied the Serengeti and his photographs were published in the National Geographic magazine in May 1986. The study took 18 months to complete.

This picture was one of the most successful. The event seems to be covered in dust and appears as a confusing scene, but the figure leaping in the foreground manages to link the animals together from above and below.

Iwago is described as ‘a virtuoso of the decisive moment�� for his ability to capture the nature of animals and their seasonal habits in his photography.

Bombay by Carl De Keyzer, 1985

This photograph appears on the cover of De Keyzer’s book India, which was published in 1987. The selection and sequencing of the pictures was not chosen by him and at the time he wasn’t happy with the results, although today it makes him smile.

The people in the car appear so happy despite the fact that they are ploughing through the water. This prompts the question of whether they know that there is trouble ahead or not.

Dirk van der Spek comments, “Laughing people in the land of Nehru and Gandhi, the land of cultural conflict between Hindus and Muslims, Sikhs, Biharis and Bengalis. The land that is also notorious for its gigantic natural and environmental disasters. Ostensibly it seems as if the people cheerfully accept these problems.”

In this respect, De Keyzer has chosen to capture the moment in the present and not look too closely at history, although it can still be found here. He has captured the joy in a moment of disaster.

Gerard Willemetz and Dani by Jacques-Henri Lartigue, 1926

This photograph has captured the enthusiastic moment as a young boy leaps over his sand castle, probably in the hopes of impressing his younger friend.

Lartigue began taking photos as a child and he continued to do so for the rest of his life. He worked within the very society which he was trying to capture which aided his success.

He was particularly intrigued by capturing frozen moments in his photography and he had an eye for small events which made great pictures.

William Boyd who writes for The Guardian describes Lartigue’s work: ‘this unique time-stopping ability of photography was what he wanted to celebrate with his pictures.’ Boyd goes on to say that Lartigue ‘showed how the snapshot could be a work of art.’

Martha Graham: ‘Letter to the World’ (Kick) by Barbara Morgan, 1940

Letter to the World was performed and choreographed by the dancer Martha Graham in 1940 and was performed at the college where she taught.

Graham had some radical ideas about dancing and thought that it needed to return to the basics again and revert back to classical dance. She believed that movement should take place around the centre of the body and she tried to renew dancing to make it palatable and relevant to her contemporaries.

You can see in this photograph that Morgan has shown Graham’s technique of movement around hte centre of the body. She is remarkably horizontal from the waist up and her skirt is flying behind her captured in motion.

Morgan photographed a lot of dancers and performers and most of her photographs show some kind of decisive moment, whether that be through an emotional look on somebody’s face or a troop of dancers caught in motion.

My thoughts

Sources: https://pixels.com/featured/a-decisive-moment-alfred-dolezal.html (12)

https://painterskeys.com/decisive_moment/ (13)

In my opinion there are three ways of describing the decisive moment. They are:

A more literal understanding of the term, as established by Henri Cartier-Bresson, where the decisive moment captures a sudden occurence of motion and hints at movement.

In a way, every photograph can be classed as a decisive moment. I think this because every time someone decides to take a photograph, a moment is frozen in time; a moment that cannot be repeated.

Lastly is what happens outside the frame. My other two criteria describe something which occurs within the photograph, but I also think that you can describe the decisive moment as what has happened to influence a picture. For example, the setting of the sun may inspire a picture of the night sky and the sunset is therefore the decisive moment.

Besides the originals, I find photographs of blurred figures moving around busy urban streets to be boring and unoriginal. It is no longer enough to shoot this if you intend to be creative as it has been done to death by amateurs and professionals alike. To make a decisive moment interesting it has to be given context or a further meaning. Showing a process or conveying a meaningful point is different from simply snapping a person mid stroll.

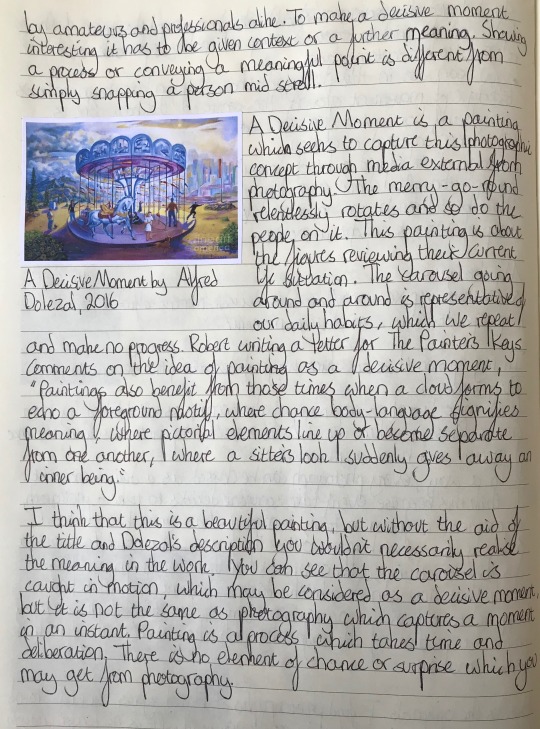

A Decisive Moment by Alfred Dolezal, 2016

A Decisive Moment is a painting which seeks to capture this photographic concept through media external from photography. The merry-go-round relentlessly rotates and so do the people on it. This painting is about the figures reviewing their current life situation. The carousel going around and around is representative of our daily habits, which we repeat and make no progress. Robert writing a letter for The Painter’s Keys comments on the idea of painting as a decisive moment, “Paintings also benefit from those times when a cloud forms to echo a foreground motif, where chance body-language signifies meaning, where pictorial elements line up or become separate from one another, where a sitter’s look suddenly gives away an inner being.”

I think that this is a beautiful painting but without the aid of the title and Dolezal’s description you wouldn’t necessary realise the meaining in the work. You can see that the carousel is caught in motion, which may be considered as a decisive moment, but it is not the same as photography which captures a moment in an instant. Painting is a process which takes time and deliberation. There is no element of chance or surprise which you may get from photography.

Hand written notes and print-outs

Bibliography

O'Byrne, R. (2014). H. Cartier-Bresson: l’amour tout court. Retrieved from Vimeo: https://vimeo.com/106009378

Cartier-Bresson, H. (1932). Behind the Gare Saint-Lazare. Museum of Modern Art, Saint-Lazare.

Wells, L. (2015, January 30). Photography: a Critical Introduction. Retrieved from ProQuest Ebook Central: https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ucreative-ebooks/reader.action?docID=1968918

Pantall, C. (2012, May 17). The Present. Retrieved from Photo-eye: https://www.photoeye.com/magazine/reviews/2012/05_17_The_Present.cfm?

Ghazzal, Z. (2004). the indecisiveness of the decisive moment. Retrieved from Zouhair Ghazzal: http://zouhairghazzal.com/photos/aleppo/cartier-bresson.htm

Jeffery, I. (2000). The Photography Book. Phaidon Press.

Editors of Time Magazine. (2016). Saigon Execution Eddie Adams 1968. Retrieved from Time 100 Photos: http://100photos.time.com/photos/eddie-adams-saigon-execution

Blue Wildebeest. (2015). Retrieved from Minden Pictures: https://www.mindenpictures.com/search/preview/blue-wildebeest-connochaetes-taurinus-herd-descending-cliff-during/0_00114286.html

Nollet, D. (2016, August 15). A conversation with Carl De Keyzer. Retrieved from Cape: http://www.cape.ag/?p=1252

Boyd, W. (2016, May 27). Snap judgment: how photographer Jacques Henri Lartigue captured the moment . Retrieved from The Guardian: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/may/27/snap-judgment-how-photographer-jacques-henri-lartigue-captured-the-moment

Barbara Morgan. (1974 – 2019). Retrieved from International Center of Photography: https://www.icp.org/browse/archive/constituents/barbara-morgan?all/all/all/all/0

Dolezal, A. (2016, March 20). A Decisive Moment. Retrieved from Pixels: https://pixels.com/featured/a-decisive-moment-alfred-dolezal.html

Robert. (2004, August 10). The decisive moment. Retrieved from The Painter's Keys: https://painterskeys.com/decisive_moment/

#henri cartier-bresson#photography#photographer#art#Liz Wells#paul graham#the present#colin pantall#zouhair ghazzal#decisive moment#eddie adams#linda connor#mitsuaki iwago#carl de keyzer#jacques-henri lartigue#barbara morgan

0 notes

Text

All Quiet on the Home Front. Colin Pantall. ICVL Studio. 2017

En caja de carton, hecha a mano, Wild Brown 450 gr, con lino grabado en cubierta ( dibujo de Isabel Tanko ). 25×20 cm. 112 paginas. Color.

Fotografías, Colin Pantall. Texto, en inglés, Colin Pantall.

Edición, Colin Pantall, Alejandro Acín.

Diseño, Alejandro Acín.

Papel Mohawk polar 120 gr. Encuadernación OTA Binding.

Prepress, Tom Groves. Impresión, PurePrint.

1° edición, con copia original firmada y numerada, 12/ 50 de la edición de suscriptores.

ICVL. Noviembre 2017.

Hoy es mi cumpleaños, y aunque ya tengo este libro desde hace unos días, lo recibo como un regalo. El que nos hace Colin al hablar de su condición de padre,

Llego a París Colin Pantall ( Bath, Gran Bretaña ) con su primer libro, All Quiet on the Home Front. Colin es fotógrafo, escritor ( contribuye al British Journal of Photography ), profesor, también tiene un blog sobre fotolibros.

No se encuentran muchos libros en los que un hombre cuenta su experiencia de padre, su relación con su hija, (Isabel, 16 años hoy), y el cambio que ha supuesto en su vida, de una manera tan honrada, bella y conmovedora.

Colin fotografía a Isabel y al hacerlo se retrata a si mismo, descubriendo a través de ella una nueva identidad de padre . Su felicidad, sus alegrías, su sorpresa ante la mirada de Isabel, sus ojos verdes ( como la cubierta del libro?), llena de energía y a ratos desafío. Sus dudas, angustias y temores ante el futuro, el reconocimiento del miedo ante la muerte, siempre presente nos dice, su vulnerabilidad confesada.

Fotografiada entre 2005 y 2017, Isabel llena todo el libro con su energía y aplomo, con momentos de evidente complicidad o simplemente en su mundo. Dentro del domicilio, en la intimidad del hogar y la luz cálida de la tarde, pero sobre todo en el exterior, en las colinas cercanas, en la playa o el bosque, donde Colin busca crear unos lazos, un sentimiento de pertenencia común. El espacio, el paisaje es tanto un terreno de complicidad como un lugar virgen de descubrimiento, donde aprender a conocerse el uno al otro, calmar sus dudas y afirmarse como padre.

Son momentos sencillos, bellos y melancólicos, porque el tiempo no se detiene. Isabel ya no será nunca más la niña que fue. Ser padre es dar y saber que tienes que renunciar… “I wish Isabel away. I always wish her back.”

Mucho mas se podría decir de este libro, de su encanto, de la fantástica naturalidad de Isabel, de la calidad de la luz y los colores, la calidez del papel que lo hace tan agradable al tacto. De lo universal y sin embargo intransferible que es la experiencia de la paternidad, y la proximidad que todos sentimos con Isabel y Colin. De la infinita ternura y gran angustia que queda plasmada en los caminos de tierra en estas fotografías. Gracias por este generoso regalo, suerte para el futuro, Colin y Isabel.

http://icvlstudio.com/product/all-quiet-on-the-home-front-signed-book

https://open.spotify.com/track/6469HvIwa0hkJqFKsFaK6Z

27 de noviembre 2017. All Quiet on the Home Front. Colin Pantall. All Quiet on the Home Front. Colin Pantall. ICVL Studio. 2017 En caja de carton, hecha a mano, Wild Brown 450 gr, con lino grabado en cubierta ( dibujo de Isabel Tanko ).

0 notes

Text

Instagram has Made Street Photography Cliche and You're the Problem

"They crave validation and are taking the quickest possible route to get it."

Now more than ever, street photography has become cliché. But what’s the solution? And more importantly, do we need one?

In an article recently published on World Press Photo, writer Colin Pantall asks: Why photograph when every picture has already been made?It’s a great question and one that highlights the impact of both an oversaturated industry and hobby. Because nowadays, everyone is a…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Photo

5th April, Venice, Italy

Speaking with my friend Colin Pantal. He is doing a project on coronavirus and he asked me to interview me and give me my point of view as Italian and Venetian

12 hours on a clock face, 12 months in a year, time is fragmented, cut into slivers we live through from one moment to the next. The first quarantine

“Did you know that quarantine was invented in Venice. Now we have it, with restrictions that have grown tighter and tighter. We can only go 200m from our home, we need a piece of paper to leave, we have to wear a mask and gloves now. Everyone has seen pictures of the clean canals of Venice, that’s preserving the tourist image of Venice. What they don’t see are the seagulls that have taken over the city and shit everywhere, or the real want. There are very few strong images of coronavirus so people don’t know what to expect. In Italy there is no social security, so people can’t pay their rent, and can’t eat – especially if you’re cooking with ingredients that are impossible to find: flour, ladyfinger biscuits for tiramisu and yeast for making pizza.

I think that Italians underestimated the seriousness of the situation because of a lack of visual images: in the beginning, there were more pictures of people singing on the balcony. We only saw the real effect of the COVID really late, just when we saw the pictures of the military tanks transporting the coffins in Bergamo and the Pope celebrating Mass in the empty Piazza San Pietro. I think it’s been a crisis that is badly represented by photography. It makes me wonder what the iconic image of this period will be. I don’t think we’ve seen it yet?"

https://www.instagram.com/p/B-msPKtlcUw/?igshid=13qhgkwrnyqcz&fbclid=IwAR2NFdGTKtFO2b4Jf3MNYDQz4l8ca498Ec41xRmhMpjQ4e0oxBpU6MVdvTg

0 notes

Link

“[In] 1988, Ilya [Kabakov] created the first version of the installation Labyrinth (My Mother’s Album) – a claustrophobic, maze-like corridor with 76 framed works hung along its walls. These showed images taken by Uncle Juda alongside fragments cut from 1950s Soviet postcards and typed excerpts from his mother’s haunting memoirs. Reflecting Ilya's inability to protect his mother from poverty and homelessness, Labyrinth (My Mother’s Album) is a dialogue – a tribute by a son to his mother, but also to all women in Soviet society.”

Via Colin Pantall

1 note

·

View note